Monads For The Rest Of Us - Part 6

In which you kill null

So you want to model functions that might fail to return a value.

Over time, developers have invented several approaches to model this:

- Returning

null, to signal that the returned value shall be ignored. - Raising exceptions to force the caller to consider alternative execution paths.

- Returning an extra value, signaling if the result is either valid or should be ignored. Think to Go’s

f, err := os.Open("filename.ext"). - Returning a Discriminated Union Type, that is a value that could take one of several predefined, distinct forms.

The monadic way is the last one: it’s about defining a type representing either a valid outcome or the absence of a result, and about providing it the semantic of a monad, so that it can be used just like all the other monads.

Maybe maybe

The monadic type Maybe shall model both the existence of a value (of type A), and the absence of a value (of type A too).

We either could use a boolean:

record Maybe<A>

{

private readonly bool ContainsValue;

internal readonly A _a;

internal Maybe(A a)

{

_a = a;

ContainsValue = true;

}

internal Maybe()

{

ContainsValue = false;

}

}

or play with the nullability of A.

The internal implementation of Maybe does not matter much: it’s enough that a version of Run and Bind is available for that implementation.

An interesting, type-safe option is to model this with a Discriminated Union Type. In F#, it would be a matter of defining:

type Option<'a> =

| Some of 'a

| None

Using the example of an Option<int>, you can read the code above as:

- An instance of

Option<int>can be created using one of the 2 available costructors,Some(n)orNone(). Some(42)represents the existingintvalue42.None()represents a missingint.- In both cases, the result is an instance of

Option<int>. - Given an instance of

Option<int>, one can always distinguish the cases and take a decision by applying pattern matching. - It’s even possible to continue the computation without distinguishing the cases, provided an implementation of

bindandcompose.

C# does not support the | type operator, but it’s easy to get close to a Discriminated Union Type playing with inheritance:

abstract class Maybe<A> { }

internal class Just<A> : Maybe<A>

{

private readonly A _a;

internal Just(A a)

{

_a = a;

}

}

internal class Nothing<A> : Maybe<A>

{

}

or, more concisely:

abstract record Maybe<A>;

record Just<A>(A Value) : Maybe<A>;

record Nothing<A> : Maybe<A>;

Return

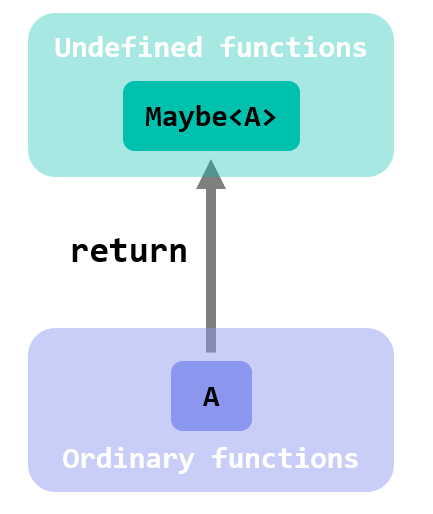

We surely need a Return function to lift an A value in the realm of the undecided functions:

Given an A value, the most natural way to elevate it in the real of the optionally-returning functions is to use the Just constructor:

Maybe<A> Return<A>(A a) => new Just<A>(a);

or design a factory method to get to:

Maybe<A> Return<A>(A a) => Just(a);

but those are implementation details that don’t alter the essence.

Run

That’s a very intersting challenge.

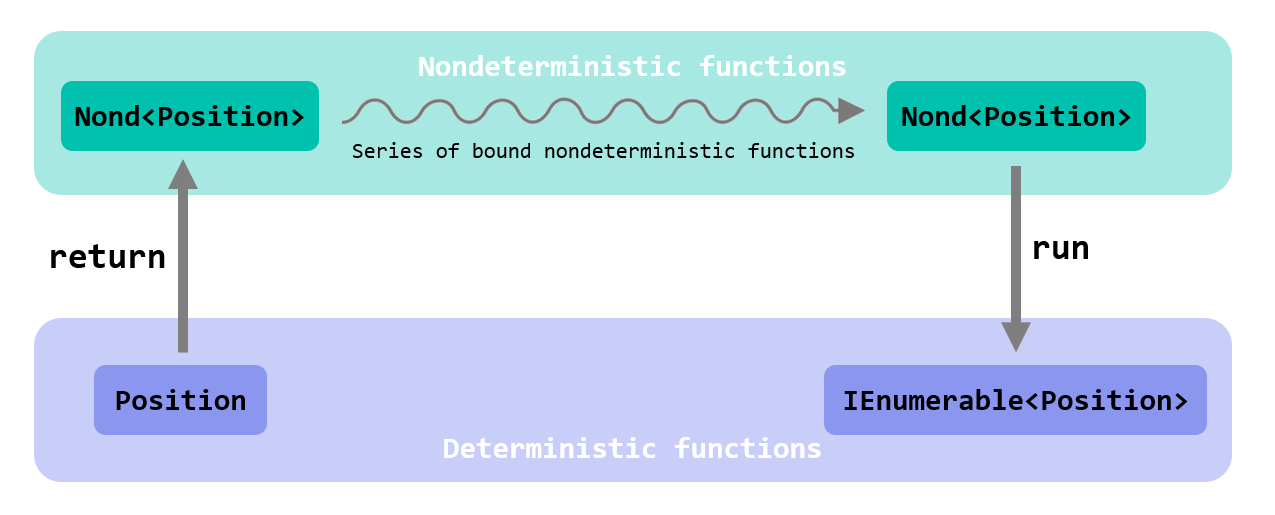

One could think that Runis the inverse of Return, and that given a Monad<A> gives back an instance of A. You might remember that I mentioned in Part 5 that Return and Run needn’t be symmetric. This was apparent for the nondeterministic functions, where running Nond<Position> returned back an IEnumerable<Position>:

If you think about it, we should expect that Return and Run cannot be symmetric: the reason we transitioned to the elevated realm of monads in the beginning was to deal with something else within our functions. Monads enable us to defer these extra actions, but when we return to the realm of the ordinary functions and values, with Run, these postponed effects must eventually occcur. And this reflects in either more than one value being produced, or something arbitrarily complex, including values of different types.

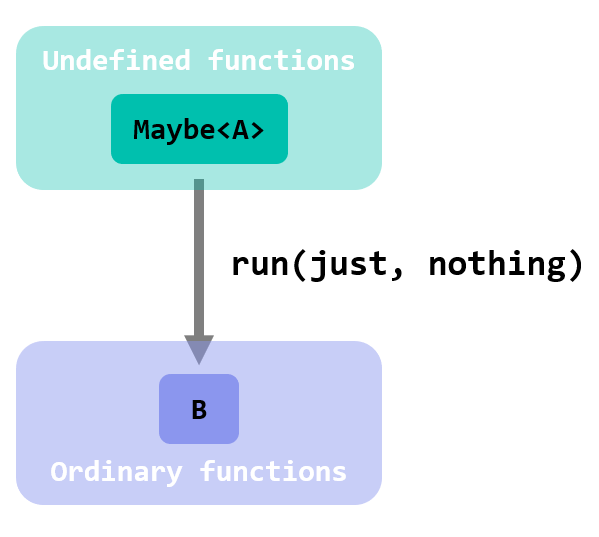

The same must happen to the run function for Maybe<A>. It’s hard to imagine it can return an instance of A: we don’t even know if there is an A value! Indeed, we used Maybe<A> exactly for the possibily to represent the absence of a value: how can it possibly generate it from the thin air?

A Run(Maybe<A> maybe) =>

maybe switch

{

Just a => maybe.Value,

Nothing => ???

};

}

A more reasonable approach is to provide Run with 2 functions, one for each possibility:

abstract record Maybe<A>

{

B Run<B>(Func<A, B> just, Func<B> nothing) =>

this switch

{

Just<A> a => just(a.Value),

Nothing<A> => nothing()

};

}

record Just(A Value) : Maybe<A>;

record Nothing : Maybe<A>;

int n = 42;

Maybe<int> maybeN = Return(42);

string result = maybeN.Run(

just: a => $"I got a {a}",

nothing: () => "I got nothing!");

Assert.Equal("I got a 42", result);

This function is usually called Match. Think about it like the following:

Maybeis about modeling the possible absence of data.- As long as a valu has been lifted, it can be processed with functions using

bindandcompose, as a matter of facts deferring the check if a resulting value has been obtained. - The moment the computation needs to brought down to the lower, ordinary world, the monad is run, and a decision must be finally taken.

- The decision is a dicotomic one: either we got a final result or we did not.

- The code must be provided with 2 alternative execution paths. Therefore the

justandnothinglambdas.

Many languages, including C# and F#, provide a native implementation for this, via pattern matching.

Bind

Based on Run, an implementation of Bind is trivial:

Maybe<B> Bind<A, B>(Func<A, Maybe<B>> f, Maybe<A> a) =>

a.Run(

just: a => f(a),

nothing: () => new Nothing<B>());

Interpret it as:

- Applying a

Maybe<A>to af :: A -> Maybe<B>function might take 2 different paths. - If the input

Maybe<A>value represented an existing value, then it makes sense to applyfto the existing value. - If the input

Maybe<A>value represented the absence of a value, there is no way to possibly applyf. All we can do is to propagate the information that there will be no result. - The caller was expecting a

Maybe<B>, so we will use aNothingrepresenting the absence of aBvalue.

Here’s how it’s used:

Maybe<string> ReturnsSomething(int a) =>

new Just<string>($"I'm {a}, I feel so young!");

Maybe<string> ReturnsNothing(int a) =>

new Nothing<string>();

// get either the value or an error message

string RunIt(Maybe<string> maybe) =>

maybe.Run(

just: b => b,

nothing: () => "No result, sorry");

Maybe<string> something = Bind(ReturnsSomething, Return(42));

Assert.Equal("I'm 42, I feel so young!", RunIt(something));

Maybe<string> nothing = Bind(ReturnsNothing, Return(42));

Assert.Equal("No result, sorry", RunIt(nothing));

Compose

You know from Part 5 that there is no need to write an implementation for Compose: it’s automatically derived by Bind.

Hooray! Less code to write! Just like for the Functor’s Map, which is just simply:

Func<Maybe<A>, Maybe<B>> Map<A, B>(Func<A, B> f) =>

a => Bind(a => Return(f(a)), a);

Congrats. Add another monad to your kit belt.

If you wanted abstraction, you got it

We repeated over and over that bind is a way to apply a (monadic) function to a (monadic) value.

Be prepared: we’re about to take a trip into the hyperuranium and shift our perspective on bind from a means of passing values to viewing it as a transformer of monadic functions.

Put on your seatbelt tight, take some dried fruit and enjoy the journey.

Jump to Chapter 7.