Variables are syntactic sugar for lambda expressions (C#)

While reading Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs, I got hit by this sentence (p. 65):

“A

letexpression is simply syntatic sugar for the underlying lambda expression”

It claims that variables definition is not a necessary language feature, and that it has been introduced only as a convenient alternative to lambda expressions.

WAT? Seriously?

Scala version | C# version

Lisp’s let

To provide you with a context: the sentence refers to Lisp’s let; you can think to let as the equivalent of C#’s var for variables initialization.

Lisp’s:

(let ((x 10)) ...

has more or less the same meaning of C#’s:

var x = 10;

That’s not strictly true, but bear with me.

Also, the same book defines “syntatic sugar” as:

“convenient alternative surface structures for things that can be written in more uniform ways”

It should be clearer now why the sentence:

“A let expression is simply syntatic sugar for the underlying lambda expression.”

if applied to C#, really would mean that the reserved word var wouldn’t be a strictly necessary language construct, as a variable initialization could be easily replaced by lambdas.

Although the explaination provided by the book revolves around Scheme, a Lisp dialect, and might not necessarily be valid with other programming languages, I found it fun enough to translate it to Scala and C#.

Guess yourself before reading

What variable initialization and lambda expressions have in common? How could one replace a variable with a lambda? They are so distant topics to me that I don’t see how one could be the syntatic sugar of the other.

I’ve got a suggestion: before reading the next paragraph, challenge yourself, and try to get an answer to the question: how could you replace local variables with lambda expressions, without using any var?

From an algebraic function to a lambda expression

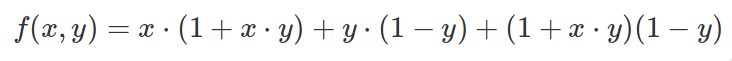

SICP starts from this algebraic function:

You can easily translate it to C# as:

static int F(int x, int y)

{

return x * (1 + x * y) + y * (1 - y) + (1 + x * y) * (1 - y);

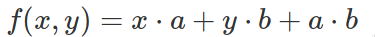

}Since 1 + x * y and 1 - y are repeated twice, you could write the same function as:

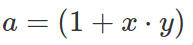

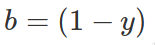

where a and b are defined as:

In C#, this could be implemented introducing an auxiliary function Helper:

static int Helper(int x, int y, int a, int b)

{

return x * a + y * b + a * b;

}

static int F(int x, int y)

{

return Helper(x, y, 1 + x * y, 1 - y);

}Notice how the auxiliary function’s body is the function in the desired, simplified form, while the value of a and b is provided by F.

Also notice that, since the auxiliary function Helper is only used by F, it could be defined as a local function, i.e. as a nested function:

static int F(int x, int y)

{

int Helper(int a, int b)

{

return x * a + y * b + a * b;

}

return Helper(1 + x * y, 1 - y);

}We had to remove x and y from Helper’s parameters, since Helper is defined within the scope of x and y. So, Helper is actually a closure.

Now, ask ourselves why we are providing Helper with a name: it is a local, internal function of F and we are not going to reuse it in any other place. We might as well define it as an anonymous function, by the means of a lambda expression, and then immediately invoke it:

static int F(int x, int y)

{

return ((Func<int, int, int>) (

(a, b) =>

x * a + y * b + a * b))

(1 + x * y, 1 - y);

}The resulting code is definetely weird and not idiomatic, but it’s correct.

Notice how we could distinguish 3 different areas in it:

- an initial segment where

aandb– the arguments of the former functionHelper– are declared - the function’s body,

x*a + y*b + a*b - a last part, where two values for

aandbare provided (that is, their initialization):

static int F(int x, int y)

{

return ((Func<int, int, int>) (

(a, b) => // arguments declaration

x * a + y * b + a * b)) // body

(1 + x * y, 1 - y); // arguments value initialization

}Observe how we are not dealing with variables, but with function arguments.

It’s at this point that the Wizard book claims:

This construct is so useful that there is a special form called

letto make its use more convenient.Using

letthefprocedure could be written as:

static int F(int x, int y)

{

var a = 1 + x * y; // variables declaration + initialization

var b = 1 - y;

return x * a + y * b + a * b; // body

}This is more conventional and familiar!

Consider the last 2 snippets. In Lisp, the latter is just syntatic sugar of the former: whenever you define a variable with let and you assign it a value, you are in fact defining a closure, whose parameter has got the provided name and value, and whose body is the code in that variable’s scope.

Woah, it makes sense… They are just the same concept, with two different syntaxes.

Implicit and explicit scopes

About scopes, I think it is worth mentioning that, in Lisp, the special form let requires the developer to explicitly define the scope of the variable. Notice the following:

(let ((b (- 1 y))) # we are assigning 1 - y to b, and also beginning b's scope

.. # body, where b is used

) # b's scope endThe very first and the very last parenthesis in this snippet delimit the variable’s scope.

In C#, scopes are rarely defined likewise explicitly. Whenever a symbol is defined with var, a scope is implicitily defined. So, when we write:

static int F(int x, int y)

{

var a = 1 + x * y;

var b = 1 - y;

return x * a + y * b + a * b;

}2 scopes are implicitily defined, as we would have written:

static int F(int x, int y)

{

{ // beginning of a's scope

var a = 1 + x * y;

{

var b = 1 - y; // beginning of b's scope

return x * a + y * b + a * b; // body

} // end of b's scope

} // end of a's scope

}I find it so sweet how a 1958’s programming language can still provide insights and interesting perspectives to modern developers. By the way, get a copy of SICP: it is a very challenging book, but it is definitely worth a read.