Monads For The Rest Of Us - Part 8

In which you achieve true enlightenment

seeing that Functors are not boxes

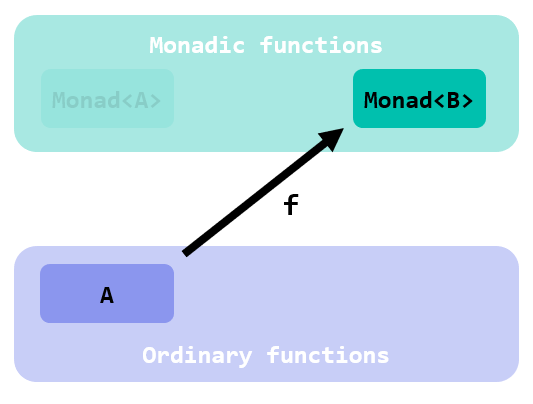

You just discovered that Bind takes crippled functions, with a leg still clinging to the old world, and fixes them elevating them so they are fully immersed in the realm of monads:

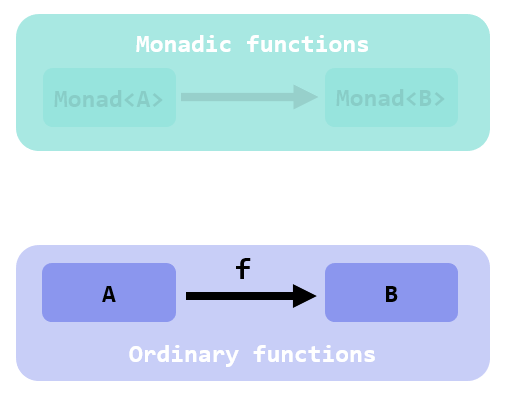

What about even more stubborn functions that have both input and output in the non-monadic world?

How can we fix them elevating to the monadic world?

Wait a sec! Why should we even fix them? We never thought that this was a problem. We always said that pure, ordinary functions are the ideal ones to deal with, the building blocks of Functional Programming.

And that’s true: by no means the desire to elevate them to the monadic realm implies they are problematic. See this differently: how to write simple, pure functions, and then have a magic way to elevate them so they can work on monadic values, no matter the effects?

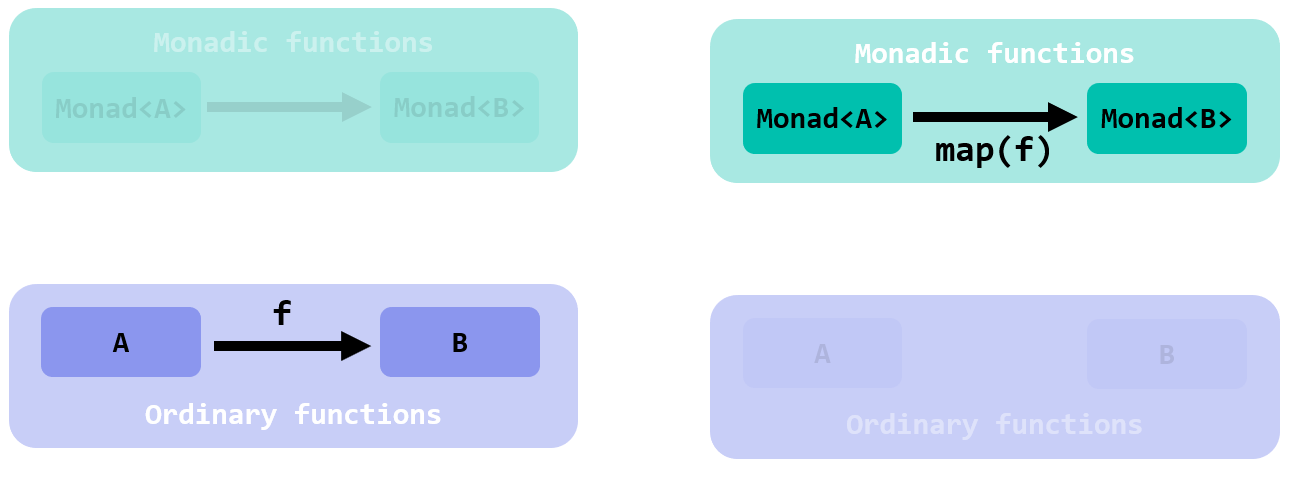

This is the first intuition: a Functor is a way to teletransport your pure functions in a monadic world, where some effects are in place.

The function that takes:

f :: A -> B

and lifts it to:

f :: Monad<A> -> Monad<B>

is called map:

Functors

Let me tell you what a Functor is, using a bit of Category Theory.

I promised that this series did not require any knowledge of Category Theory, and I won’t go back on my word. I swear that it will be super easy.

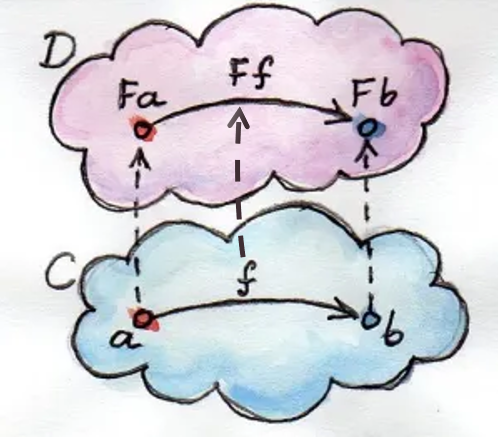

I love this image by Bartosz Milewski, from the chapter Functors of his book Category Theory for Programmers:

I slightly modified it adding a missing arrow.

Interpret it as follows:

- There are 2 worlds,

CandD. In our case, the world of ordinary functions and values, and the world of monadic functions. - In the world of ordinary functions there is a function

ffrom the typeato the typeb - In the world of the monadic functions, there is another function called

F f, from the typeF ato the typeF b. In our previous diagrams we used the C# style, and we called themMonad<A>andMonad<B>. This does not alter the essence

A Functor is a mapping between these 2 worlds.

In Category Theory for Computing Science, Michael Barr and Charles Wells write:

“A functor F : C -> D is a pair of functions […]”

- mapping the types of

Cto the types ofD - and the functions of

Cto the functions ofD

while preserving some rules, that I’m omitting for simplicity.

Let me stress again: a functor is a pair of functions. A functor is not a thing: it’s two. It’s the mapping that teletransports your types and your functions to the monadic world.

Of course, this is the mathematical definition. Projected to the programming language world, you need some way to implement this idea. No surprises that you can find a wide variety of implementations, from classes implementing a Functor interface, like in language-ext:

[Typeclass("F*")]

public interface Functor<FA, FB, A, B> : Typeclass

{

/// <summary>

/// Projection from one value to another

/// </summary>

/// <param name="ma">Functor value to map from </param>

/// <param name="f">Projection function</param>

/// <returns>Mapped functor</returns>

[Pure]

FB Map(FA ma, Func<A, B> f);

}

or a type classe called Functor, like in Haskell:

class Functor f where

fmap :: (a -> b) -> f a -> f b

which captures both the mapping of functions, with fmap and the mapping of values, with f, or traits, like in Scala Cats:

trait Functor[F[_]] extends Invariant[F] { self =>

def map[A, B](fa: F[A])(f: A => B): F[B]

override def imap[A, B](fa: F[A])(f: A => B)(g: B => A): F[B] = map(fa)(f)

final def fmap[A, B](fa: F[A])(f: A => B): F[B] = map(fa)(f)

def widen[A, B >: A](fa: F[A]): F[B] = fa.asInstanceOf[F[B]]

def lift[A, B](f: A => B): F[A] => F[B] = map(_)(f)

[...]

}

The implementation is not essential, but it is interesting to notice how it often influences the way functors are described and defined. Here’s a collection of examples from real random articles:

- “a functor is simply something that can be mapped over”

- “a Functor is some kind of box that can hold generic data and map a function”

- “a functor is a type that can map itself to another version of itself using a mapping function”

- “A functor is a container of values”

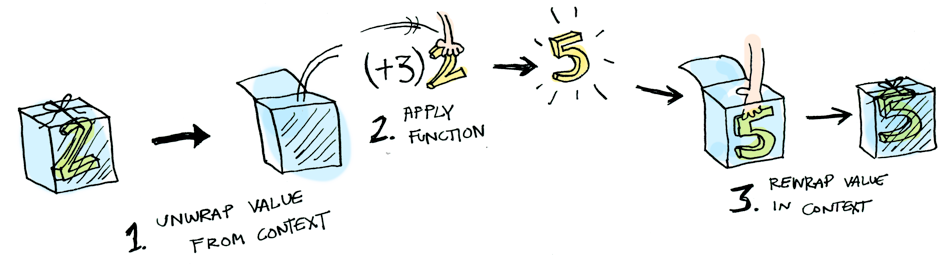

The most popular way to visualize functors is using boxes, as in Functors, Applicatives, And Monads In Pictures:

This is all good. But I recommend: don’t forget that these are only approximations and visualization stratagems.

The box metaphor holds true in many scenarios, but easily falls short in others, leading to situations that can be quite perplexing.

Before implementing functors for our IO, Undetemined and Maybe cases, let’s see with some code those 2 different perspectives on Functors.

Functor as a mapper

Take a simple function string -> int:

Func<string, int> length = s => s.Length;

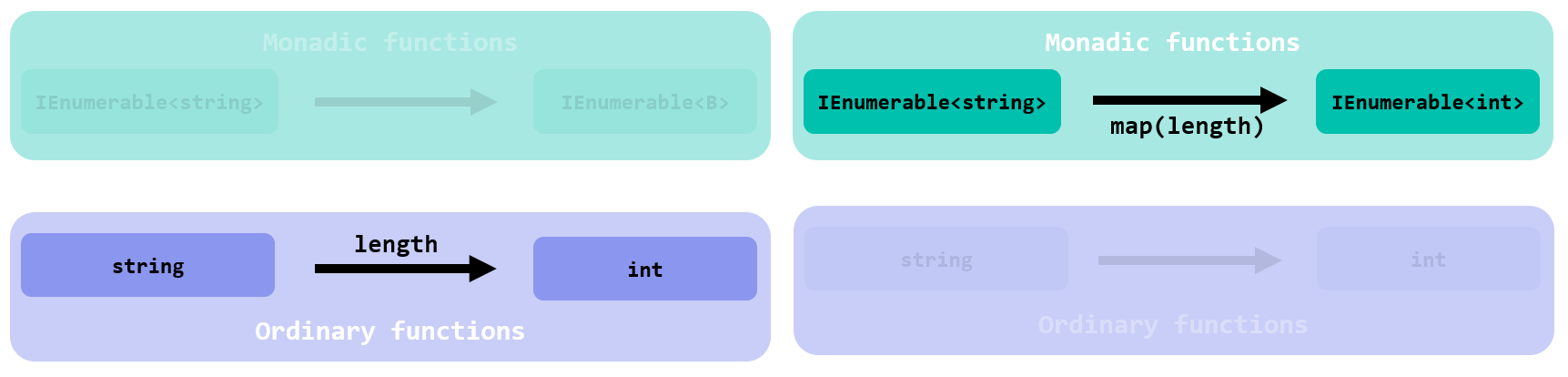

We want to map it work with IEnumerables, and make its signature

IEnumerable<string> -> IEnumerable<int>

That is, we want to elevate it to the world inhabitated by types modeled by the IEnumerable monad:

Do you see how this type-signature transformation perfectly match the goal of Map?

Let’s implement it:

internal static class FunctorExtensions

{

internal static Func<IEnumerable<A>, IEnumerable<B>> Map<A, B>(this Func<A, B> f)

{

IEnumerable<B> ApplyFunctionToAllItems(IEnumerable<A> aa)

{

foreach (var a in aa)

{

yield return f(a);

}

}

return values => ApplyFunctionToAllItems(values);

}

}

Given a function string -> int:

Func<string, int> length = s => s.Length;

Map transforms it to a function IEnumerable<string> -> IEnumerable<int>:

Func<IEnumerable<string>, IEnumerable<int>> functorialLength = length.Map();

IEnumerable<string> values = new[] { "foo", "barbaz", "" };

IEnumerable<int> lengths = functorialLength(values);

Assert.Equal(new[] { 3, 6, 0 }, lengths);

Functor as a box

Before developing Map for the 3 monads we defined, IO, Nond and Maybe, it might be interesting to see why Functors are often described using the metaphor of a box. Bear with me: we are going to perform a series of refactoring moves. At the end we will get to an implementation of a Functor seen as a way to map a function to the content of a container.

The reason why I want to get there via refactoring is to stress that the 2 points of view are 2 faces of the same coin.

With Rider / ReSharper, move your cursor on yield and apply “To collection return”:

Func<IEnumerable<A>, IEnumerable<B>> Map<A, B>(this Func<A, B> f)

{

IEnumerable<B> ApplyFunctionToAllItems(IEnumerable<A> aa)

{

var items = new List<B>();

foreach (var a in aa)

{

items.Add(f(a));

}

return items;

}

return ApplyFunctionToAllItems;

}

On foreach, “Convert into LINQ-expression”:

Func<IEnumerable<A>, IEnumerable<B>> Map<A, B>(Func<A, B> f)

{

IEnumerable<B> ApplyFunctionToAllItems(IEnumerable<A> aa)

{

return aa.Select(a => f(a)).ToList();

}

return ApplyFunctionToAllItems;

}

Feel free to remove the ToList() call:

Func<IEnumerable<A>, IEnumerable<B>> Map<A, B>(Func<A, B> f)

{

IEnumerable<B> ApplyFunctionToAllItems(IEnumerable<A> aa)

{

return aa.Select(a => f(a));

}

return ApplyFunctionToAllItems;

}

On ApplyFunctionToAllItems apply “To Expression Body”:

Func<IEnumerable<A>, IEnumerable<B>> Map<A, B>(Func<A, B> f)

{

IEnumerable<B> ApplyFunctionToAllItems(IEnumerable<A> aa) => aa.Select(a => f(a));

return ApplyFunctionToAllItems;

}

Again on ApplyFunctionToAllItems, apply “Inline method”:

Func<IEnumerable<A>, IEnumerable<B>> Map<A, B>(Func<A, B> f)

{

return aa => aa.Select(a => f(a));

}

On f “*Replace with method group”:

Func<IEnumerable<A>, IEnumerable<B>> Map<A, B>(Func<A, B> f)

{

return aa => aa.Select(f);

}

On return, apply “To Expression Body”:

Func<IEnumerable<A>, IEnumerable<B>> Map<A, B>(Func<A, B> f) => aa =>

aa.Select(f);

That’s interesting! We just discovered that Map is natively implemented by LINQ’s Select.

To see this clearly, in the calling site:

var lengths = length.Map()(values);

inline Map():

var lengths = ((Func<IEnumerable<string>, IEnumerable<int>>)(aa => aa.Select(length)))(values);

Go on the => and apply To Local Function:

IEnumerable<int> Func(IEnumerable<string> aa) => aa.Select(length);

var lengths = ((Func<IEnumerable<string>, IEnumerable<int>>)(Func))(values);

You can simplify the last line removing a bit of extra type annotations:

var lengths = Func(values);

Inline Func and, voilà:

var lengths = values.Select(length);

You can interpret Select as the function that maps length to the content of values, an IEnumerable<string> seen as a container of string values.

In the Chapter 9 we will finally implement map for IO, Nond and Maybe.

Resources

- Bartosz Milewski - Category Theory for Programmers

- Michael Barr, Charles Wells - Category Theory for Computing Science

- Functor as defined in language-ext

- Functor as defined in Scala Cats

- Functors, Applicatives, And Monads In Pictures