Fun with IEnumerable - Part I - Funny collection behaviors

This is the first installment of a short series about using and abusing co-routines with IEnumerable. In this first episode we see how to make this puzzling test pass:

[Test]

public void puzzling_test()

{

IEnumerable<string> strings = SomeStrings;

Assert.AreEqual(new[] { "Foo", "Bar", "Baz" }, strings.ToArray());

var test1 = strings.Select(s => new string(s.ToCharArray()));

Assert.AreEqual(new[] { "Foo", "Bar", "Baz" }, test1.ToArray());

var test2 = strings.Select(s => "" + new string(s.ToCharArray()));

Assert.AreEqual(new[] { "Foo", "Bar", }, test2.ToArray());

// Hey, what happened to Baz??

try

{

var test3 = strings.Select(s => new string(s.ToCharArray()) + "");

Assert.Null(test3.ToArray());

}

catch (PlatformNotSupportedException)

{

Assert.Pass();

}

var test4 = strings.Select(s => new string(s.ToCharArray()) + "");

Assert.AreEqual(new[]

{

"Argument Foo of type System.String is not assignable to parameter type int32",

"Argument Bar of type System.String is not assignable to parameter type int32",

"Constructor 'Baz' has 0 parameter(s) but is invoked with 0 argument(s)"

}, test4.ToArray());

}

Actually, I used an outrageously and dishonest trick. It’s super easy to replicate once you realize that consuming an IEnumerable is not just traversing a collection, but actually executing a computation.

IEnumerables are computations

Take

IEnumerable<int> numbers = new List<int> { 1, 2, 3 };

foreach (var number in numbers)

{

Console.WriteLine(number);

}

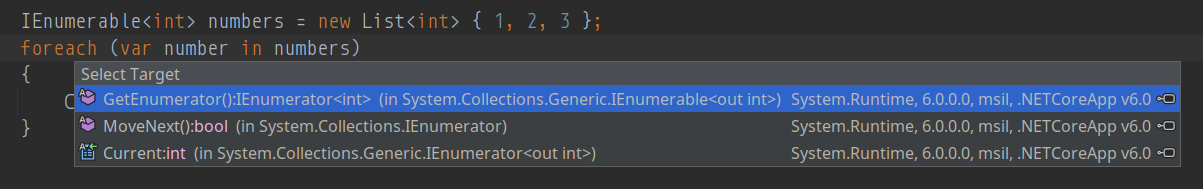

You can ask JetBrains Rider to navigate to the foreach definition, only to discover that there isn’t any. Instead, you will be directed to the IEnumerable interface

Going deeper, you’ll eventually smash your face on the List implementation of IEnumerable:

public bool MoveNext()

{

List<T> list = this._list;

if (this._version != list._version || (uint) this._index >= (uint) list._size)

return this.MoveNextRare();

this._current = list._items[this._index];

++this._index;

return true;

}

object? IEnumerator.Current

{

get

{

if (this._index == 0 || this._index == this._list._size + 1)

ThrowHelper.ThrowInvalidOperationException_InvalidOperation_EnumOpCantHappen();

return (object) this.Current;

}

}

The gist is: each implementation of IEnumerable has got its own specific code that is executed when the collection is cycled. foreach is somehow kind of syntactic sugar over invoking GetEnumerator(), MoveNext() and Current .

Of course, you can have your own custom implementation of IEnumerable performing whatever arbitary code you wish. When someone cycles on your collection, your arbitrary code is executed.

Do you already guess where this is going to lead us?

Co-routines are equivalent to IEnumerables

An easy way to see this is to convice ourselves that:

IEnumerable<int> numbers =

new List<int>{1, 2, 3};

is equivalent to

IEnumerable<int> generate()

{

yield return 1;

yield return 2;

yield return 3;

}

IEnumerable<int> numbers = generate();

When cycling the collection, foreach would just execute the code of the co-routine generate(), line by line, each time stopping to the next yield return. The client of numbers would not tell the difference: it’s just a collection, isn’t it?

If you add some arbitrary statement, it will be executed as well:

[Test]

public void arbitrary_code_executed_while_cycling_a_collection()

{

string sideEffect = "";

void FunctionWithSideEffect()

{

sideEffect = "FunctionWithSideEffect() was fired!";

}

IEnumerable<int> generate()

{

yield return 1;

yield return 2;

FunctionWithSideEffect(); // Hey, I'm executing some arbitrary statement!

yield return 3;

}

IEnumerable<int> numbers = generate();

foreach (var number in numbers)

{

Console.WriteLine(number);

}

Assert.AreEqual("FunctionWithSideEffect() was fired!", sideEffect);

}

It shouldn’t surprise you that the same occurs when using LINQ:

numbers.Select(n => n * 2).ToArray();

Notice, though, that LINQ is lazy: therefore, as long as the collection is not materialized with ToArray(), no code is run.

Side effects and Multiple Enumeration

What happens if you cycle the collection multiple times? Easy guess: your arbitrary code (and possibly its side effects) will be triggered multiple times.

private int countNumberOfInvocations;

IEnumerable<int> StatefulEnumerable

{

get

{

countNumberOfInvocations++; // A side effect

yield return 1;

yield return 2;

yield return 3;

}

}

[Test]

public void a_stateful_collection()

{

IEnumerable<int> numbers = StatefulEnumerable;

foreach (var number in numbers){} // hidden side effect

foreach (var number in numbers){} // hidden side effect

foreach (var number in numbers){} // hidden side effect

Assert.AreEqual(3, countNumberOfInvocations);

}

Side effects are an insidious element when playing with IEnumerables. Guess what could happen with the following code:

class Client

{

private readonly IMyRestApi _myApi;

internal Client(IMyRestApi myApi)

{

_myApi = myApi;

}

IEnumerable<string>.Buy(string[] products)

{

return

from productCode in products

where _myApi.CountInStock(productCode) > 0 // a safe API call

let success = _myApi.Buy(productCode) // a less safe API call

select productCode;

}

}

public interface IMyRestApi

{

int Buy(string productId);

int CountInStock(string productId);

}

[Fact]

public void unexpected_api_calls()

{

var myApi = Substitute.For<IMyRestApi>();

myApi.CountInStock("any product").ReturnsForAnyArgs(1);

var client = new Client(myApi);

IEnumerable<string> boughtProducts =

client.Buy(new[] { "book", "jewel", "pc" });

foreach (var p in boughtProducts) // hidden side effect!

Log.Information($"Bought: {p}");

Console.WriteLine($"Bought a total of {boughtProducts.Count()} products"); // another hidden side effect

myApi.Received(2).Buy("book");

myApi.Received(2).Buy("jewel");

myApi.Received(2).Buy("pc");

}

Well, this sucks: only by logging and writing to Console, you actually bought some products twice. This is why the IDE warns you with the Possible multiple enumeration of IEnumerable Code Inspection.

Legit uses

Co-routines can be used for legit cases, such as generating an infinite list of random numbers:

IEnumerable<int> random()

{

var random = new Random();

while (true)

yield return random.Next(100);

}

calculating the Fibonacci series

IEnumerable<int> Fibonacci()

{

var fibs = fibonacci().Prepend(1).Prepend(1);

var tail = fibs.Skip(1);

var zipped = fibs.Zip(tail, (a, b) => a + b);

foreach (var z in zipped)

{

yield return z;

}

}

Assert.AreEqual(

new []{2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89},

Fibonacci().Take(9).ToArray());

}

or repeating some values in a dynamic way:

static class TimesExtension

{

internal static IEnumerable<T> AdNauseam<T>(this T value)

{

while(true)

yield return value;

}

}

[Test]

public void legit_case()

{

var strings = "I stalk you".AdNauseam().Take(100);

Assert.AreEqual(100, strings.Count());

}

Notice that the collection is not materialized until Count() or ToArray() are evaluated.

Crooked uses

But you can also do fancy stuff like:

private int countInvocations;

IEnumerable<int> UnstableCollectionOfNumbers

{

get

{

if (countInvocations++ % 2 == 0)

{

yield return 1;

yield return 2;

yield return 3;

}

else

{

yield return 1;

yield return 2;

}

}

}

[Test]

public void an_unstable_collection()

{

var numbers = UnstableCollectionOfNumbers;

Assert.Equals(3, numbers.Count());

Assert.Equals(2, numbers.Count());

Assert.Equals(3, numbers.Count());

Assert.Equals(2, numbers.Count());

}

You can easily return completely different collections at each invocation, raise exceptions, call external APIs and the like.

Your fantasy is the limit.

The trick revealed

So, coming back to the initial puzzling test, it should be clear that everything revolves around how the IEnumerable SomeStrings was implemented.

```csharp

[Test]

public void puzzling_test()

{

IEnumerable<string> strings = SomeStrings; // <== Hey, what's behind this property? Show me the code!

I cowardly omitted it, I’m such a jerk. Here it is:

private static int count;

internal static IEnumerable<string> SomeStrings

{

get

{

count++;

if (count == 1 || count == 2)

{

yield return "Foo";

yield return "Bar";

yield return "Baz";

}

else if (count == 3)

{

yield return "Foo";

yield return "Bar";

// yield return "Baz";

}

else if (count == 4)

{

throw new PlatformNotSupportedException();

}

else if (count == 5)

{

yield return "Argument Foo of type System.String is not assignable to parameter type int32";

yield return "Argument Bar of type System.String is not assignable to parameter type int32";

yield return "Constructor 'Baz' has 0 parameter(s) but is invoked with 0 argument(s)";

}

}

}

That’s is.

And now for something completely

We could take advantage (?) of this and get to something totally dumb and useless, such as an ill implementation of Dependency Injection via the encapsulating of an Action into a collection.

That’s the topic for the part 2.